Rene Descartes should be symbolically thanked by the creators of The Matrix for propagating the idea of ’a brain in a vat’ in Western culture. Descartes, often called the father of modern western philosophy, begins his magnum opus, Meditations on First Philosophy, with a famous thought experiment that might lead one to think that we are not in control of our minds, and therefore cannot trust our own judgments that suggest that we exist. Descartes puts it as follows:

“Nevertheless, the belief that there is a God who is all powerful, and who created me, such as I am, has, for a long time, obtained steady possession of my mind. How, then, do I know that he has not arranged that there should be neither earth, nor sky, nor any extended thing, nor figure, nor magnitude, nor place, providing at the same time, however, for [the rise in me of the perceptions of all these objects, and] the persuasion that these do not exist otherwise than as I perceive them?” (First Meditation)

Given the interest that this imagery elicited nearly four hundred years later in The Matrix trilogy, it seems clear that humanity is at times both troubled and fascinated by this possibility.

Even though this is usually used to imply that we have no control over our lives, or live in a world of illusion, I want to consider the imagery on another level. For some of us, easily recognizable among philosophers and other academics, I think it is not far from the truth that we are just brains in vats. We just happen to call the vats ‘bodies.’ Consider that for many, one of the main goals of one’s life is to strengthen the muscle that is one’s brain, either for its own sake or for some instrumental purpose. On this view, what is the fundamental difference — absent the implications of illusion — between carrying a brain around in a vat, nurturing it along the way in the company of other brains and their products (e.g. books, conversation, etc.), and living the life of an academic?

I don’t see this as being inherently negative. The moral judgment, if attached to this image at all, has much more to do with the instrumental purpose this knowledge is being put to, or not being put to. Some people simply desire to strengthen the muscle between their ears instead of the various muscle groups focused on by athletes and fitness buffs.

Or, as Smith puts it, I am an “idealist”

I find the suggestion that an academic – or any human being, for that matter – can be reasonably understood as a “brain in a vat” deeply troubling. Such an image suggests that a person is reducible to only one element of themselves. Extending your metaphor with the athlete, it suggests that the olympic runner is only a great pair of legs. And yet, there has been significant research demonstrating that an athlete’s success is not reducible to one element of her physique; her performance is significantly affected by her mental state, her diet, her relationship with her coach, how much sleep she got the night before etc. Similarly, the academic’s success is dependent on her physical well-being and her economic condition (which allows her to spend time just sitting and thinking), as well as her mental state. As more academic writing begins to contain a self-reflexive element, I would argue that there is data to demonstrate that the very content of an academic’s thought is heavily influenced by a variety of external factors. The issues she becomes interested in, as well as the data that she is able to obtain, are influenced just as much by her life experiences (what she sees, what she suffers, who she know, who she loves etc.) as they are by her mental abilities.

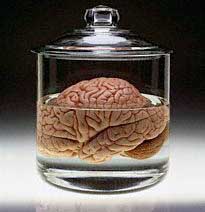

You write, “what is the fundamental difference — absent the implications of illusion — between carrying a brain around in a vat, nurturing it along the way in the company of other brains and their products (e.g. books, conversation, etc.), and living the life of an academic?” But such a question misrepresents the reality. A brain in a vat lives a solitary, entirely self-contained existence. Consider the image you posted – how could this brain engage with anything? It has no mouth to speak or eyes to read. It is protected entirely from the external stimuli such as need, pain and conflict that often spur meaningful thought. I realize that I am pushing your metaphor to an almost absurd point, but I think such a push is necessary. Only people, complexly embodied beings that they are, are able to engage in the types of relationships you envision as necessary for nurturing thought.

The willingness to casually reduce any person to only one element of themselves is not only a misrepresentation of reality, but one which I find insidious. While you expressly say that you intend no moral judgement, inherent in such a move is a willingness to objectify others, to say that only one element of their life or work is important and/or that only that element truly reflects who they are (which is to say nothing of the scores of problems, including the denigration of the body and the devaluation of certain kinds of work, that have been connected to the mind/body dualism in Cartesian thought which seems to motivate your post here). On such a view, the academic can no longer be a father, a lover of jazz music or a basketball coach. He is no longer lonely or beloved. He cannot be suffering from chronic illness, nor can he love to cook his friends extravagant meals. He is just a “brain in a vat.” To me, such a move is not only a sad reduction of the academic person, but also impoverishes our understanding and appreciation his thought.

These points are well made. The only clarification in order is to say that I meant that SOME academics, SOME of the time they are engaged in purely academic activities, might identify with the brain-in-a-vat metaphor more positively than it is portrayed in The Matrix trilogy. This does not preclude having many other facets contribute to what he or she does as a person.